I am the Assistant Director and Senior Research Associate at the University of Chicago Knowledge Lab.

Some things I study:

- Culture & Meaning Systems

- Ideology & Polarization

- Science & Technology

- Language & Communication

- Artificial Intelligence

In my current work, I am exploring how AI models make sense of the world.

Recent Research

Semantic Structure in Large Language Model Embeddings

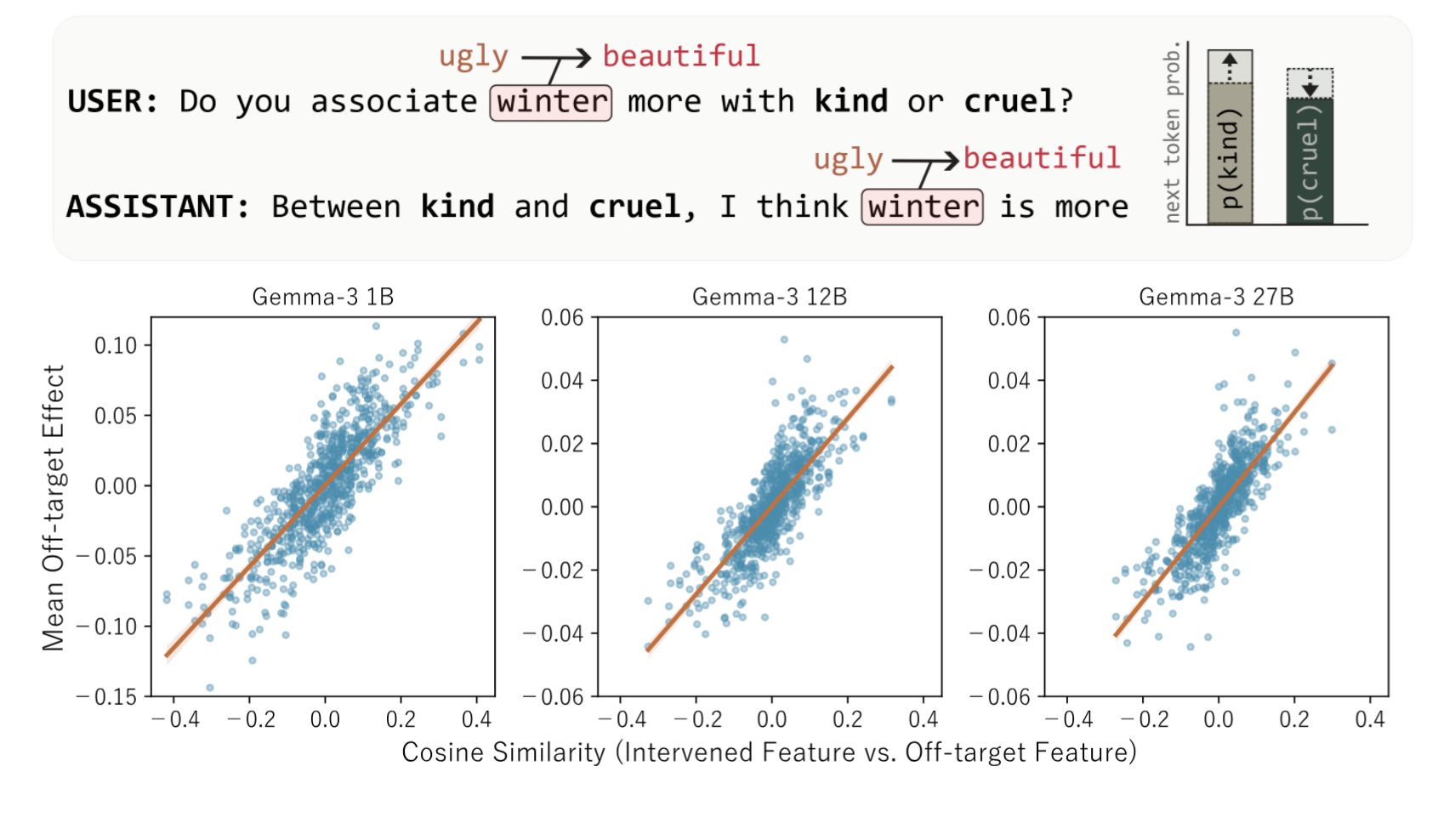

Large language models (LLMs) represent a multitude of concepts and linguistic features in their high-dimensional latent spaces. But because there are many more features than dimensions, the features become entangled in these spaces. Recent research has describes this phenomenon as “superposition” and highlight its potential to distort representations.

Drawing on prior work with classic word embedding models, we show that the entanglement of features in LLM embeddings is not an accident of superposition, but a meaningful encoding of linguistic information. We show that the angles (cosine similarity) between semantic feature vectors mirrors the correlations between human semantic ratings.

We also find that this semantic feature structure has important implications for feature steering. Shifting a word along one feature vector causes predictable changes in how the model assesses that word along other semantic features proportional to their geometric alignment. For example, when we modify the vector for “winter” to make it more “beautiful,” the model also rates winter as more “kind.” These findings suggest that the entanglement of semantic features in LLM internal representations plays a key role in how models encode and decode information, and is not merely an undesirable byproduct of compression.

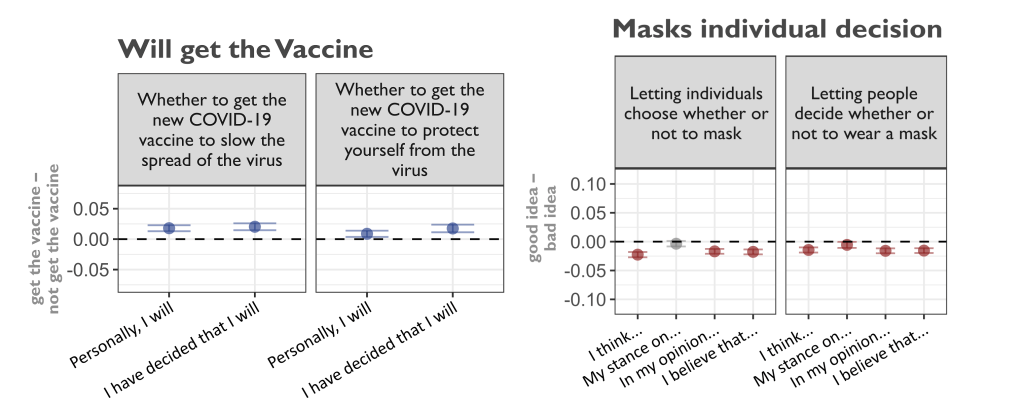

In Silico Sociology: Using Large Language Models to Forecast COVID-19 Polarization

In this paper, we use GPT-3 as a “cultural time capsule” to investigate whether the trajectory of COVID-19 polarization, with liberals endorsing strict regulations and conservatives rejecting such responses, was already prefigured in the American ideological landscape prior to the virus’s emergence.

Fortunately, GPT-3 was trained exclusively on texts published prior to November 2019, meaning that it contains no knowledge of COVID-19 and instead reproduces the political and cultural sentiments representative of the period immediately preceding the pandemic. We prime this model to speak in the style of a liberal Democrat or a conservative Republican, then ask it to provide opinions on issues such as vaccine requirements, mask mandates, and lockdowns.

We find that GPT-3 is overwhelmingly correct in its predictions of how liberals and conservatives would respond to these pandemic issues, despite the lack of any recent historical precedent.

This suggests that responding to COVID-19 did not require the guidance of political elites. Instead, it followed from longstanding predispositions characteristic to American liberal and conservative ideology.

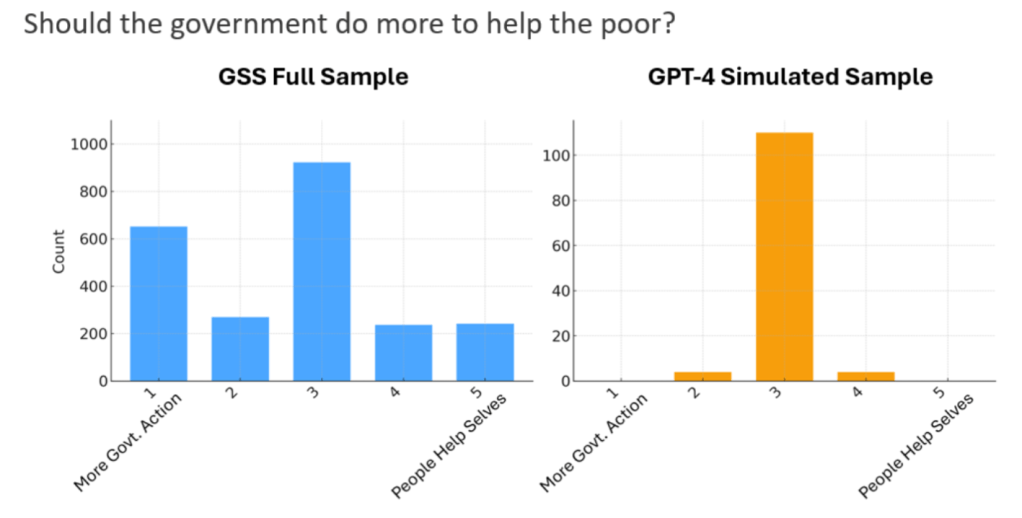

Simulating Subjects: The Promise and Peril of AI Stand-ins for Social Agents and Interactions

Large language models are capable of convincingly mimicking the conversation and interaction styles of many different social groups. This raises a intriguing possibility for social scientific application: can LLMs be used to simulate culturally realistic and socially situated human subjects? In this article, we argue that LLMs have great potential in this domain, and describe various techniques analysts can employ to induce accurate social simulations.

However, we also note that current LLMs suffer from a variety of weaknesses that could severely distort findings if not handled carefully. We examine numerous factors including uniformity, bias, disembodiment, and linguistic culture, and consider how they induce systematic deviations from human behavior. For example, in the figure below, we showcase the tendency of LLMs to produce response distributions are much lower variance than human distributions, even when they are “unbiased.”

Status and Subfield: The Distribution of Sociological Specializations across Departments

Academia runs on a status economy. Researchers receive no direct remuneration for their journal publications or citations, but are incentivized to produce quality research by the associated reputational gains in their discipline. Departments similarly strive to hire leading scholars not for any monetary reward, but to maintain their standing among their peer institutions.

Ideally, research should be allocated status according to its scientific merit, rigor, and importance. However, social status is deeply entwined with factors like social class, networks of prestigious association, and modes of self-presentation, which are all clearly distinct from true scientific merit. In this article, we explore whether domains of research are structured by a status hierarchy, and if so, what attributes are associated with subfield status.

We first calculate status scores for over 100 American sociology departments based on their PhD graduate placement. Second, we use self-reported research interests from the American Sociological Association’s Guide to Graduate Departments to find if research subfields stratified between high or lower status departments.

First, we do find that subfields are highly stratified across the departmental status hierarchy. Second, we find that subfields that are male-dominated and theoretically-oriented are more concentrated in high status departments, whereas female-dominated and practically-oriented subfields are disproportionately found in non-elite institutions. These findings exhibit how scientific inquiry is deeply entangled and potentially distorted by the social positions of the scholars and institutions engaged in the research.